Vulnerable yields

The yield gap is closing, and has reached its narrowest point since 2011. What's next?

The narrowness of the yield gap – defined as the difference between prime yield and the 10-year interest rate – is not down to a prime-yield decline in Oslo over the past year. On the contrary, yield for the best office properties in the capital has remained stable at 3.25 per cent.

However, yields in a number of other segments and locations around Norway have been on the move over the past year. The second half of 2021 was strong, and yields were under substantial pressure in many cases.

A number of investors are looking at the other large Norwegian towns. But the search for yield has also lured them to less central hunting grounds. No less than 36 per cent of the transaction volume last year lay outside Norway’s four largest cities. By comparison, this proportion was 18 per cent in 2020 and averaged 21 per cent over the past five years.

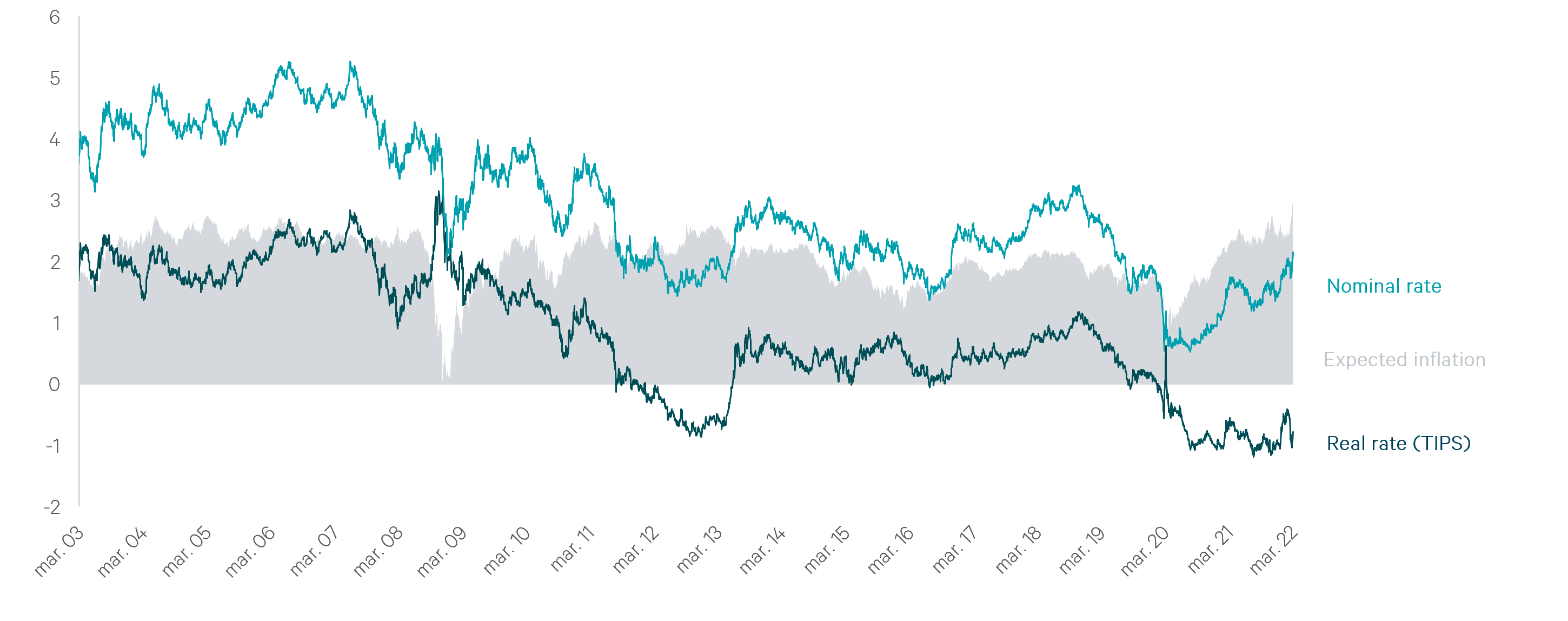

The fact that the yield gap in the capital has nevertheless narrowed naturally reflects the uptick in interest rates. Since bottoming out in the summer of 2020, the 10-year swap rate has risen by about 200 basis points – and by 100 bps since 30 November 2021.

Long-term rates in the USA are setting the pace. If we look at developments since the summer of 2020, the 10-year rate there has risen by 162 bps while the real rate (Treasury inflation-protected securities - Tips) only increased by 40 bps.

In other words, increased inflation expectations have been largely responsible for driving the interest rate rise during this period when viewed overall. Inflation expectations – in other words, the average over the next 10 years – have risen from about 1.6 per cent to 2.9 per cent over 18 months.

Unfortunately, we do not have inflation-protected government bonds in Norway and therefore cannot measure this so precisely here. If increased inflation expectations are driving interest rates, property yields will be less exposed.

Naturally, the war in Ukraine has contributed to great uncertainty on many fronts. The 10-year interest rate fell by about 20 bps at the outbreak of the war, but have since increased above pre-war levels. The real rate, however, is lower than mid-February.

Although today’s low real interest rate supports the pricing when viewed in isolation, it also illustrates the vulnerability of the market. The rate has fallen to a much lower level over the past two years as a result of the central bank’s aggressively expansive monetary policy during the pandemic. That has resulted in a sharp growth in value in many markets. But it also helps to make pricing more exposed when the central bank takes its foot off the accelerator.

If inflation proves a bigger problem in the USA than in Norway, we could risk importing higher real interest rates. Nominal rates could be pulled up without any corresponding change in the inflation or growth outlook for the Norwegian economy.

Naturally, some factors are also pulling in a positive direction. First, the office rental market is strong, with increased demand, lower supply-side growth and rising rents. Second, the CPI-mechanism in leases protects against that part of the interest-rate rise which can be attributed to increased domestic inflation expectations.

Nevertheless, we cannot avoid the reality that yield rests to a great extent on a very low real interest rate and is therefore vulnerable to a tightening in monetary policy.