“Everyone” looking to buy

Few pure logistics transactions have occurred so far this year, but a look at the deals being done indicates that the market for such properties is red-hot. And supply shortages may well be helping to put further pressure on prices.

Only a handful of logistics properties have changed hands since 1 January. At the same time, we often hear that demand is record-high. So the question is why sales are not higher. The answer probably relates to a relatively restricted market and last year’s very high volume of transactions.

Roughly speaking, the total market value for all logistics buildings in Greater Oslo is about 11 per cent of the corresponding figure for office properties in the same area. If we look at transaction volume, about 12 per cent of the logistics market changed hands in 2020. The corresponding figure for offices was 3.6 per cent.1 A mismatch clearly exists between supply and demand in the logistics segment and, because this is a small investment universe, changes in demand probably have a stronger effect on prices.

Value for logistics properties has developed more strongly than in all other segments. Like such markets as offices and part of the retail segment, low alternative returns and cheap financing have helped to stimulate demand in the transaction market. While the pandemic has raised questions about the future role of both offices and physical retail outlets, however, everyone agrees that demand for warehouse and logistics space will continue to grow.

Moreover, secure cash flows over long periods have been high on the wish list in a time of great uncertainty. The average duration of leases for logistics properties sold in 2020 was more than 10 years. By comparison, the average for offices was just below seven.

The big appetite has put pressure on yields, and the gap down to both retail and office segments is lower than it has been for more than a decade. Prime yield for logistics properties fell over the past 12 months by no less than 50 basis points to 4.25 per cent.

New space requirements

Developments in retailing have left their mark on space requirements in the logistics segment. Towards the end of last year, for example, it became clear that Oda (formerly Kolonial.no) was bringing forward the development of a new warehouse in Lier which will double this grocery supplier’s capacity. The new 18 000 m² facility has already been sold to Denmark’s NREP Logicenters.

The strong growth in online retailing has also created fertile soil for new delivery concepts. Expectations by end users are constantly increasing, while technological innovations are enhancing supply-chain efficiency. One consequence is the growth of “last-mile” delivery players, who are often looking for locations which allow them to reach the largest number of householders in the shortest possible time – centrally in the Groruddalen district, for example.

In addition to a central location, players set stringent requirements for a site’s accessibility. This type of logistics is characterised by a high turnover ratio, with many deliveries and a large number of transports. Their shelves are refilled by heavier lorries during the morning and emptied by bike couriers and smaller vans later in the day. Such a model also makes big demands on technology and automation, and the terminals are often laid out differently from traditional warehousing. Ceiling height is less important, for example, because deliveries involve individual goods rather than pallets.

Supply side

A long-standing trend has seen logistics and mixed-use properties centrally located in eastern Oslo being forced to give way to housing, retail and cultural purposes. This has led to supply shortages within Oslo’s city boundaries. The combination of little supply and high demand is reflected in vacancy, which was only 1.2 per cent inside the city limits at 31 December 2020.

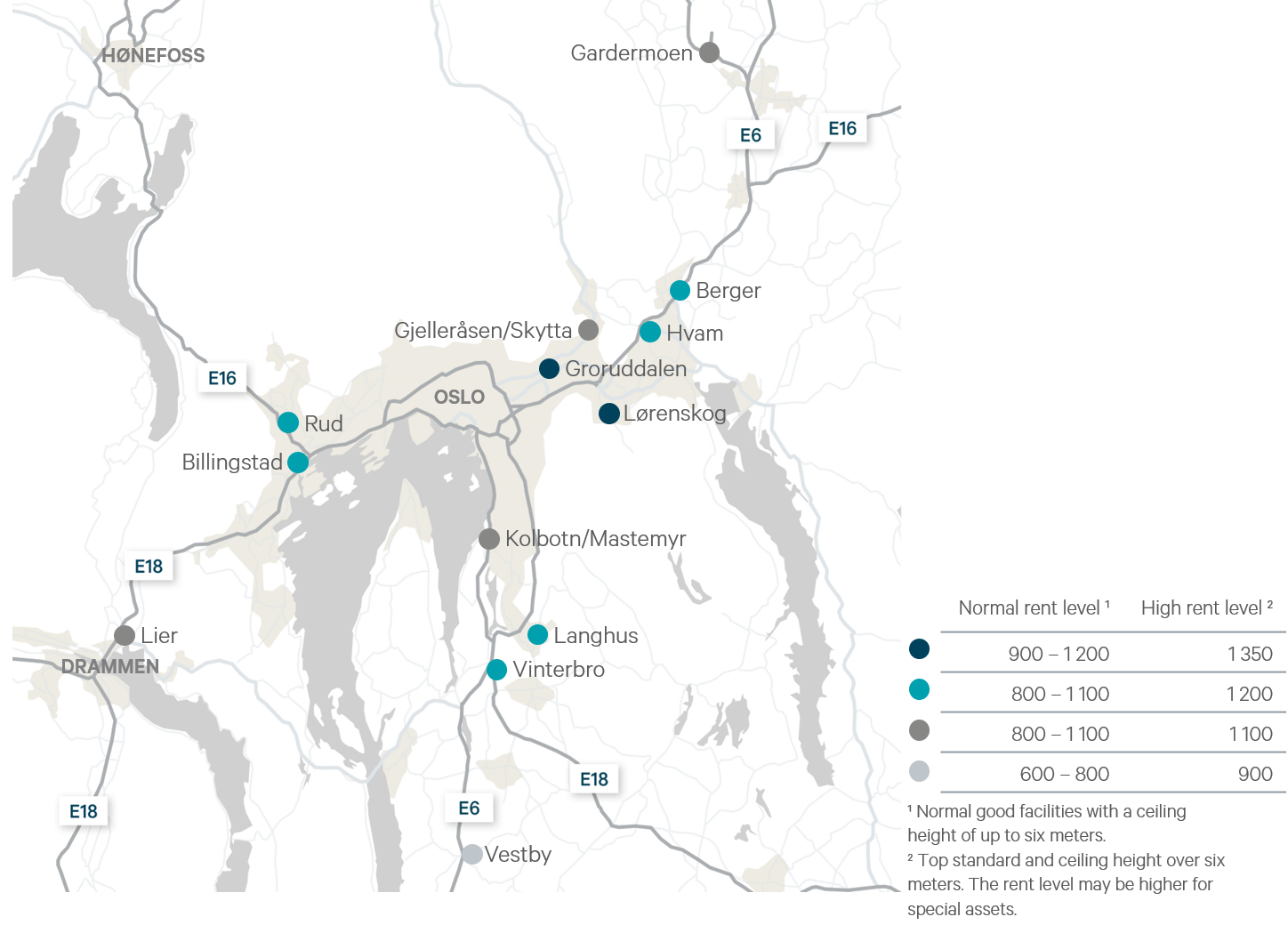

One consequence of restricted supply in Oslo has been the establishment of new logistics clusters along the main arteries in and out of the capital. However, the best-established clusters also have few available spaces left, and many of the sites with planning permission in areas such as Berger and Vestby are already fully developed.

However, availability of properties is much better further out. A number of sites with planning permissions remain undeveloped at Gardermoen. Availability is also good further south – around Drøbak and Moss, for example.

Vacancy in existing logistics buildings is low for the moment, even when those outside Oslo’s boundaries are included. The overall figure is 3.2 per cent.

Rent levels

Roughly speaking, we see three development trends for rents. Where attractive areas along the motorways are concerned, such as Berger, rent levels are stable. When you get a long way out, however, they are subject to some negative pressure. The combination of a lot of sites and declining yields contributes to this. In central Groruddalen, where demand is rising and the net expansion in space is small or negative, rents are rising slowly.

We expect these trends to persist. At the same time, with rents having been driven down to such a low level in certain areas and building costs on the rise, we are perhaps reaching a floor for the rents newbuildings can command in some places.

The signs are that space requirements among warehouse users will continue to expand. Those who can offer large, practical sites which are not too far outside Oslo will be able to secure attractive tenants

1 The calculation is based on the total building stock in the Greater Oslo area and average rent and yield levels in these areas.